Learning from my Early Astronomical Missteps

Folks in my family tend to be obsessive. At least, I’m sure it looks that way to my own children as they’ve witnessed my streaky hobbies over the years, from genealogy to watches to running to, lately, astronomy.

But I can’t think of too many worthwhile pursuits that I just randomly picked up. Usually, there’s a deep and involved history behind what I devote my time to.

My long genealogy binge, which yielded a trove of photographs and factoids and stories, many of which I captured on my blog, Whispering Across the Campfire, was a natural extension of my interests as a journalist and writer.

Watches were objects that tickled my fancy as far back as the first ones I strapped to my wrist — the ones that featured Snoopy on the dial or a pull-back car or a transforming robot!

And though it took me several years to get my butt off the couch, distance running was something I first learned to love as a pre-teen, striding alongside my dad before actively pounding the pavement in high school and college. Returning to form, then, is all the more sweet for the effort I’ve put into it.

That’s something I’d say is common to any of the experiences I collect and cherish: if it’s not a little hard to get, if there isn’t knowledge earned in the pursuit, is there anything much to it?

Stargazing certainly ticks the boxes for yielding more surprises and magic and lore the more time I invest in it. Although I’m keenly aware of all I have yet to learn and perfect, being able to chart how far I’ve come, and enjoy my astronomy sessions all the more for what I can do better now, are indications this latest obsession isn’t likely to dry up in the near future.

On a recent Scout campout I was only too tickled to share my knowledge with kids and parents who lined up to take a peek through my telescope. We’d been blessed with two mild, clear, calm November nights in a row, which is saying something for South Dakota, and it was a nice change to have company as I skimmed the scope across the sky as the world turned and constellations and planets wheeled overhead.

“No, that’s not the north star. Polaris is over there. That’s Jupiter — cool, right? Take a look, you can see four of its biggest moons in the scope and its cloud bands.”

“No, that’s not Orion — it won’t come up for another hour or two, over there — East. Take a look at the Pleiades instead. It’s one of my favorites.”

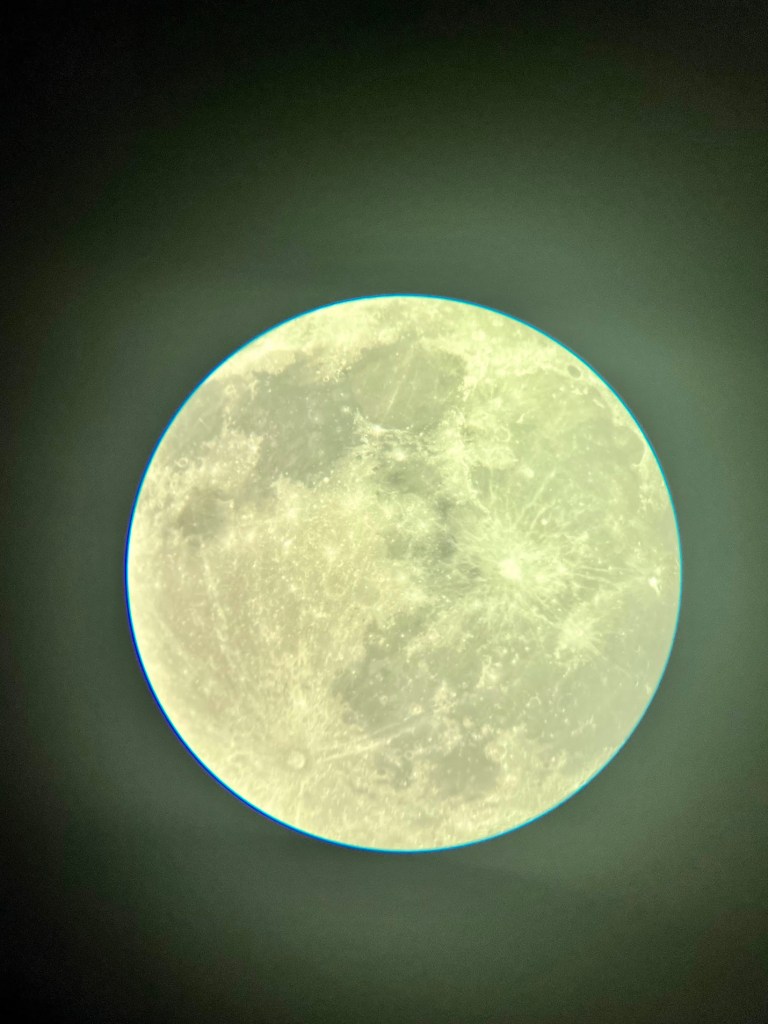

“No, you can’t see the flag the astronauts planted on the moon, but let’s take a look up close. See that huge crater — check out the little bump in the middle of it — that’s where some of the lunar rock settled after the moon was hit and that crater formed.”

It was gratifying when the scouts said they were inspired to dust off their telescopes and binoculars at home and take a new look at the sky. One of them asked how I’d gotten to know so much. (HA! Wow.) The answer, of course, is complicated because I always think of how much I don’t know, and still get wrong, but now have a deeper trove of resources I turn to to get it right, and get myself unstuck.

I definitely didn’t start out that way. So I thought I’d share a few of my tips and tricks here, starting with a look back at my more memorable missteps.

Learning by Doing — or Not Quite Doing

Like some of my other “obsessive” hobbies, I’ve been entranced by space and the night sky since I was a kid.

I had a bedroom planetarium in elementary school — you know, the kind with a globe and lightbulb inside that would rotate and cast the stars on your walls and ceilings. As a young Boy Scout myself I earned my Astronomy merit badge under dark skies at summer camp, and had to identify multiple constellations each year to earn my Pipestone award at Seven Ranges Scout Reservation in Ohio. I remember first being able to pick out the Lazy W of Cassiopeia, the great square of Pegasus, the seven sisters of Pleaides, and to distinguish the big dipper from the little.

Lying on my back in the grass I was stunned to learn the fast-moving, blinking lights in the sky were satellites. And I remember first bending to the eyepiece of the big Dobsonian cylinder and seeing Saturn, actual Saturn, clear as anything. It was electrifying, at camp. But I mainly left that hands-on experience of astronomy at camp.

As the years went on, I indulged my fascination for space in other ways. The Right Stuff is one of my all-time favorite movies, not to mention Gravity, and Interstellar, and the classic 2001: A Space Odyssey. I would rewind shows like The Universe constantly, trying to catch and understand every detail of our world and worlds beyond. My favorite parts of sci-fi books like The Long Earth were when explorers went beyond the complexity of multiple earths to tackle the-even-more complex multiple Mars-es and moons (or lack thereof).

Beyond fiction, there’s enough to blow my mind in books like Phil Plait’s Death from the Skies, about the many ways the universe can kill us (in gory detail), and, just last year, Under Alien Skies, which combines Phil’s scientific knowledge with his masterful way of making life on other worlds, well, come alive for the reader. As a casual, but committed, space-watcher, tuning in to the various iterations of Plait’s Bad Astronomy blogs and newsletters has helped me keep on top of the latest interstellar discoveries.

My heavenly interest even has cross-over appeal — the first “grown-up” watch I bought for myself was the Bulova Lunar Pilot, the alternative moon watch to Omega, celebrating the astronaut who toted one along on his 1971 moon mission as a backup, only to press it into service when the crystal popped off of his NASA-issue Omega. What a story, huh? And a nice-looking watch.

So, passively at least, I always had an eye toward the stars. But I started to get an itch for hands-on exploration — or as much as we can do from the ground — during the Jupiter-Saturn “Grand Conjunction” of 2020. I’d bought a nice set of binoculars a couple years before, but never tried them at night. On the night of conjunction I called the wife and kids into the car and we drove southwest, away from the lights of Sioux Falls, as the sun set. With clouds starting to crowd the sky, I directed my wife to pull over on the side of a farm field and I jumped out and pointed skyward.

I’m sure I thought I was going to see something like what I saw in that big Dobsonian at summer camp years before. Um, not nearly. And I found my hands were so irritatingly twitchy that the combined bulbs of Saturn and Jupiter were so many jittering streaks. We drove home, cold, disappointed. But I started dreaming of putting more power up to my eyes the next time I bothered scoping the heavens.

When Your Best Intentions End up in the Lake

Throughout 2020-22, after my failed Grand Conjunction chase, I browsed telescopes on Amazon. From refractors to reflectors to Dobsonians to Schmidt-Cassegrains, I didn’t exactly understand everything I was reading, yet, but I knew I wanted something powerful, but also simple to use. Something I could set up, easily, but with a reliable payoff.

Black Fridays and Cyber Mondays and Christmases and New Years came and went and I just couldn’t manage to pull the trigger. Probably I had a hunch of the type of learning curve I was in for. And just wasn’t ready.

But as we prepared for a return to scout camp in Minnesota, where for a week I could count on brilliant skies above Many Point Lake, impulse took over. I was hooked by Celestron’s Travel Scope package, which came in 60mm, 70mm, or 80mm, and came with a couple eyepieces, a cellphone attachment for photography, heck, even a tripod and backpack for easy transport. I chose the biggest size (80mm), and punched in my order so the scope would arrive before we left for camp.

Now, this scope isn’t all bad. Wait — what am I saying? — this scope fails on several critical levels.

Do you learn something about setting up a scope, and pointing it, and focusing it? Well, yes.

Do you start to scratch the stargazing itch? Well, yes, but in a torturous way that leaves you even more unfulfilled for the ways the scope, as configured, can’t possibly measure up.

At the time, I hadn’t yet discovered John A. Read’s excellent Learn To Stargaze books, videos and website. But John dispels any hopeful notions for this scope with his five minimum requirements:

- Does the telescope have at least 4 inches of aperture (about 100mm)? (NO! 80mm, no matter how you measure it, is NOT 100).

- Does the telescope come with a red-dot or bullseye finder? (no finderscopes!) (NO! The finderscope, in fact, would barely stay in the same spot and the thumbscrews broke almost immediately.)

- Can the telescope’s mount move effortlessly left-right, and up-down and attach to the telescope with a vixen style dovetail? (No EQ mounts for beginners.) (No! This is a pan-handle tripod meant for cameras.)

- Can the telescope balance precisely on the mount and stay fixed in place when released? (no camera tripods or yoke & rod mounts) (NO! The tripod was SO jittery that even looking at stationary objects on land was nearly impossible.)

- Can the telescope point straight up, and if it’s a refractor, does it include a 90-degree diagonal? (AH! This is a 45-degree diagonal, meant for bird watching and land sites. In fact, the last page of the manual says the scope is not for stargazing. WHAT?)

Actually, the manual says:

“Your telescope was designed for terrestrial observation. … Your telescope can also be used for casual astronomical observing which will be discussed in the next sections.”

(And then the manual ENDS.) !!!

Well, I guess I was warned.

My early trial with the scope ended with me accidentally breaking the tripod, with pieces ending up in the lake off the dock where I had hopefully set up. Probably for the best.

As John demonstrated when testing the 60mm version of this scope, it demonstrably fails the five criteria above. Although he was able to salvage it with multiple, pricy upgrades for the fun of it.

So, I resigned myself to learning more about what’s needed in a proper telescope and stargazing setup before regrouping (and re-budgeting) for a different telescope purchase. But I wasn’t ready to completely scrap my Travel Scope.

Instead, awhile after I’d upgraded to a bigger scope and set myself down the path to even more time and monetary investment in the hobby, I made three modifications on this first scope that make it at least workable for seeing and photographing targets like the moon:

- I bought a heavy-duty tripod that cost more than the telescope itself and allows for micro-adjustments up and down, and side to side, crucial when manually tracking anything in the sky (since the Earth, and thus, we, are always moving)

- I attached the 90-degree diagonal from my new scope to the old scope, once I’d upgraded the new scope’s diagonal, so I could actually point the scope up at the sky without lying on the ground or breaking my neck

- I attached the laser finder from my new scope to the old scope after another upgrade on the new scope (are you sensing a pattern here in the astronomy hobby? You should be), and applied what I’d learned from reading and watching and practicing finding objects and resolving them in the scope

After a few months on the real scope, and the above upgrades, I was able to set up the Travel Scope next to the new “big daddy” and enjoy the contrasting views of the Moon, even snapping a few (awful) photos of it.

I haven’t taken that first scope out since — I’ve been too busy trying new things out with the upgraded scope. But that’s another chapter in this story.