Here, There & In My Chair: Jupiter

Next to Saturn, Jupiter is probably the surest way to get a newbie to gasp when looking at the view through a good telescope.

When I draw out my biggish Celestron Nextstar 8 SE on campouts and beckon the scouts over to take a peak, having a reliable lineup of planets to parade by can usually guarantee a line of eager astronomy converts. Double stars and clusters? Not as much.

For several months this year, the usual crowd-pleasers were on the wrong side of the Earth, and hence, our skies here in North America, as we made our annual journey around the Sun. But, starting in late Summer, Saturn began rising in the East before midnight. And lately, Jupiter, Mars, Uranus and Neptune have joined the procession, earlier and earlier.

In an 8-inch scope, using a 10mm to 15mm lens, Jupiter reveals orange and white cloud bands, and even the Great Red spot if you time it right.

Saturn is typically golden-hued, or bright yellow, its ring system nearly edge-on this year and next, appearing a lot like the handles, or separate stars Galileo initially recorded.

I’ve been in favor of treating my focal reducer as more or less permanently affixed to my scope, which renders planets smaller but in crisper focus. Adding a Barlow just puts more layers of glass in a considerably dimmer view, but it can render those closest gas giants a bit bigger.

Not so with the other planets. Mars is a bright, vaguely reddish orb, lately at its farthest point from Earth. No icecaps, yet, for me. And Neptune and Uranus are distinct blue-purple and blue-green discs, with maybe a large moon visible. Still breathtaking to be fixing my eyes on other worlds near to our own — just not very photogenic.

That’s another attraction of gazing at the Big Daddy in our solar system through a scope, or even a good pair of binoculars: you can see worlds rotating around that other world: Jupiter’s biggest moons. And that’s a fine thing to take a photograph of. The other night, just before 4 a.m., I set up my Seestar S50 across the lawn from my big visual scope and zoomed in on Jupiter.

Here: Jupiter, Europa, Io, Callisto, Ganymede

I first tried to catch Jupiter — and Saturn — through binoculars during the Great Conjunction of 2020, fascinated that I’d be able to see them both in the same spot, and maybe spy some moons as well.

That frantic rush-hour chase proved fruitless, and started me on my deeper dive into astronomy. Now, with better tools and more practice, I’m not only at ease in snagging Jupiter when it’s available to snag, but knowing what I’m looking at, too.

In even a decent, cheap telescope, or good pair of binocs (with a steady hand), the way Jupiter’s moons arrange themselves in a straight line on either side of the big planet is striking. You’re getting the tiniest glimpse of the orbital motion astrophysicists have pored over for centuries — and a clearer view than Galileo Galilei had when he discovered the moons in the 17th century.

From Nasa.gov:

Peering through his newly-improved 20-power homemade telescope at the planet Jupiter on Jan. 7, 1610, Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei noticed three other points of light near the planet, at first believing them to be distant stars. Observing them over several nights, he noted that they appeared to move in the wrong direction with regard to the background stars and they remained in Jupiter’s proximity but changed their positions relative to one another. He later observed a fourth star near the planet with the same unusual behavior.

By Jan. 15, Galileo correctly concluded that they were not stars at all but moons orbiting around Jupiter, providing strong evidence for the Copernican theory that most celestial objects did not revolve around the Earth. In March 1610, Galileo published his discoveries of Jupiter’s satellites and other celestial observations in a book titled Siderius Nuncius (The Starry Messenger).

That didn’t work out so well for Galileo, as depicted in artwork from the National Geographic heading this post, as try as he might to explain this evolving view of the heavens to the Church, and despite the evidence right in front of their eyes, what he was formulating was heresy in theirs. Galileo would live the rest of his life under house arrest.

Last weekend, through my own scope, the Galilean moons were neatly lined up, from Europa and Io at bottom left, to Callisto and Ganymede up upper right. No more than distinct, orderly specks, but unmistakably there. And clearly revolving around our neighboring planet. Take that, Cardinals.

There: A Lot More Moons to See

Galileo documented his nightly observation of Jupiter and its satellites until he’d settled for himself that these weren’t three, and then four, background stars but moons in their own right.

More from Nasa.gov:

As their discoverer, Galileo had naming rights to Jupiter’s satellites. He proposed to name them after his patrons the Medicis and astronomers called them the Medicean Stars through much of the seventeenth century, although in his own notes Galileo referred to them by the Roman numerals I, II, III, and IV, in order of their distance from Jupiter. Astronomers still refer to the four moons as the Galilean satellites in honor of their discoverer.

The German astronomer Johannes Kepler suggested naming the satellites after mythological figures associated with Jupiter, namely Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, but his idea didn’t catch on for more than 200 years. Scientists didn’t discover any more satellites around Jupiter until American astronomer E.E. Barnard found Jupiter’s fifth moon Amalthea in 1892, much smaller than the Galilean moons and orbiting closer to the planet than Io.

It was the last satellite in the solar system found by visual observation – all subsequent discoveries occurred via photography or digital imaging. As of today, astronomers have identified 79 satellites orbiting Jupiter.

Freaking 79, right? When I was a kid I had a placemat or coloring book, or both, that listed the number of moons then known around the planets. Maybe — maybe — Jupiter was up to the teens then in satellites. Amazing how discovery is a journey that never ends.

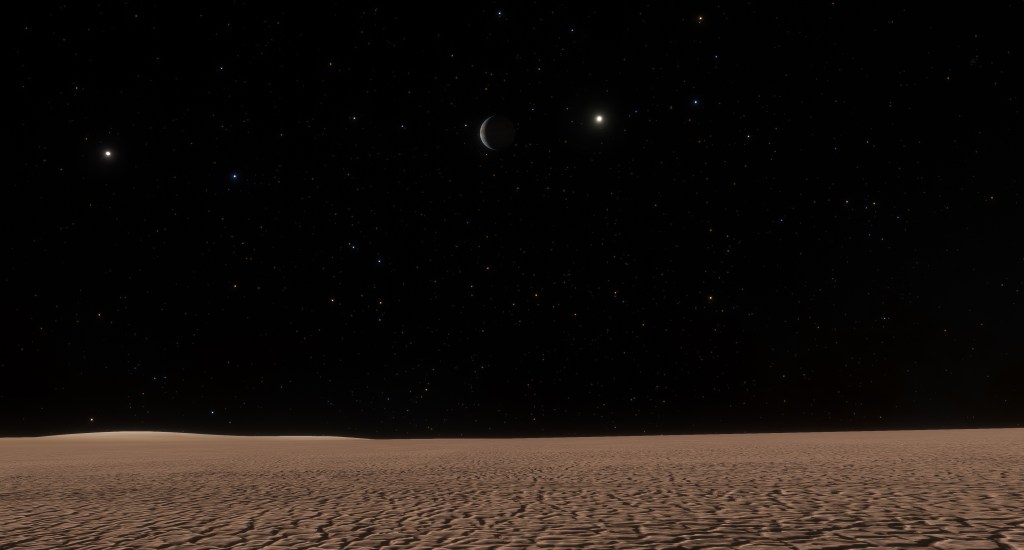

In my own exploration of our solar system neighborhood up close, through simulation software Space Engine, I’ve thrilled in flying out to the planetary system, then landing on moons to take shots of Jupiter and other moons visible. In the photos below, we see Jupiter from Thebe orbited by Callisto, Metis and Europa; then from Callisto spying a crescent Jupiter overhead; and finally, to Metis to see moon Amalthea orbiting above the giant.

And In My Chair: Crescent Jupiters & Volcanoes (oh my)!

There’s just something about seeing Jupiter, in all its glory, the way we see our Moon from Earth, rising, in phases, setting, that brings you full circle: how we’re just another stop on the planetary highway, after all.

Still, I prefer the view from Earth, of seeing Jupiter as the bright, starlike, shadow-inducing beacon that rose last night before 11 and knowing, that if I cared to look closer, whole worlds upon worlds would reveal themselves.

Here, from “in my chair” utilizing Space Engine, are successive glimpses of Jupiter from volcanic Io, after dark on Ganymede, and from frozen Europa, featuring another crescent, setting Jupiter and Jupiter eclipsing the Sun. Are these the kinds of visions Galileo dreamt about? And that we are destined, one day, to explore firsthand?