Here, There & In My Chair: C80

Part of the fun in my journey as “Telescoping Man” the past few years has been spending enough time squinting into an eyepiece pointed at the heavens so that certain targets become familiar friends — enough that I move on to discover a whole new class of astronomical sights.

Just like the constellations I had to identify each summer long ago at Scout camp, I came to recognize my calibrating stars throughout the year, from Arcturus to Altair, and Polaris to Betelgeuse; and the main galaxies and asterisms, like the Summer Triangle, and the Big Dipper (arcing to Arcturus), and the Kite of Bootes, the butterfly of Hercules, and Cassiopeia’s constant lazy W.

As I worked through the Messier catalog of clusters, and galaxies, and nebula, I also noticed the objects indexed in the New General Catalogue (NGC) and Caldwell Catalogue, and recorded coordinates of my favorite stars in the SAO (Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory) catalog, since they could be punched in to my Celestron NextStar telescope for easy slewing.

The sky’s a big place, after all, and there’s ever deeper layers to explore.

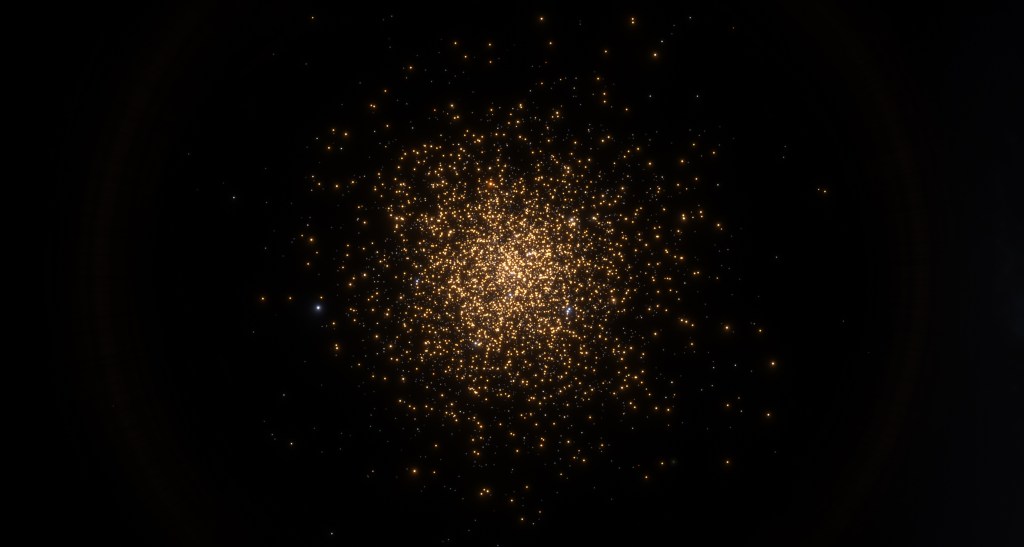

Such is the case with the Caldwell 80 star cluster, better known as Omega Centauri. A spring sight in the Northern Hemisphere, it’s typically only visible in southern latitudes, and for only a few precious hours after dark.

I couldn’t resist toting my Seestar S50 imaging telescope along on our annual vacation to North Carolina’s Grand Strand. Blessed with several clear nights with an early moonset, I plotted what typical early June constellations and Deep Sky objects I’d image from the top deck.

Here: Golden Light from 10 Million Stars

Red Antares gleamed directly south over the ocean, bringing all the clusters and nebula of Sagittarius within view. But as I swept west toward the haze of Myrtle Beach lights, checking my phone’s software for what else I could suck in with the scope’s camera sensor, I noticed, low in the horizon, a star cluster that just happened to be our galaxy’s biggest and brightest.

I’d gotten used to marveling at M13 in Hercules, and the Double Cluster in Perseus, and the myriad fuzzy balls of light dotting the sweep of the Milky Way during summer. But here was one to allegedly put them all to shame, normally only visible to those just north and south of the equator this time of year. Intrigued, I planned to point the scope at it almost as soon as the sky grew dark — before it could dip out of sight.

Caldwell 80, or C80, better known as Omega Centauri, lies about 17,300 light years away in the Centaurus constellation. It measures about 500 light years in diameter, and boasts some 10 million stars.

In its center, the stars are packed so tightly the average distance between them is only about .1 light year, solidifying C80’s status as biggest and brightest.

There: Star Light, Star Bright

Omega Centauri is about 12 billion years old, and has been known on Earth since the time of Ptolemy, who thought it was a bright star. German cartographer Johann Bayer gave the cluster its name in 1603.

Edmund Halley, of comet fame, rediscovered the cluster in 1677, recognizing it as a nebula. English astronomer was first to correctly identify it as a globular star cluster in 1838.

It appears nearly as large as the full moon in the sky, with a visual magnitude of 3.7 — typically visible to the unaided eye, that is, if you’ve got dark skies and a southerly latitude.

With Space Engine, of course, I was able to fly to Omega Centauri in a few seconds, and take in its splendor up close “from my chair.”

And In My Chair: I Spy a Black Hole!

One fun aspect of observing within our simulated galaxy in Space Engine is to enjoy night skies littered with stars when you happen to land on a planet or moon in a system moving through a globular cluster. Imagine that: it would be like shutting off the lights in your alien vacation home only to have the heavens lit up with giant fireflies.

Astronomers on Earth, though, have discovered something even more remarkable about Omega Centauri: evidence of a medium-sized black hole in its center.

From orbiting as well as ground-based telescopes, astronomers at the Max-Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany and the University of Texas at Austin have measured the movements of stars in the bright core and found evidence of a black hole of about 40,000 solar masses.

These measurements, along with the unusual presence of stars of varying ages — not typical in globular clusters — support the notion that Caldwell 80 may not be a cluster at all, but a dwarf galaxy that was stripped of its outer stars.

I stumbled upon a black hole in C80 flying around in Space Engine, and snapped the above pics.

Let’s go out on a literally eerie note: the electronic piece Caldwell 80 from composer Alp Nystrom.

Leave a comment