Here, There & In My Chair: the Pleiades

One of the ways I first started to learn the night sky — and fall in love with stargazing — was by needing to identify more and more constellations each year at Boy Scout summer camp.

As part of earning the Pipestone honor at Seven Ranges Scout Reservation in the Buckeye Council, we needed to identify in the field an increasing number of plants, animals, insects and constellations. We’d start, in year one, identifying four constellations, then 6, and then 8, and finally serving as troop astronomer or in another position of leadership to help other scouts learn the skies — and everything they needed to know to get along in a week at camp.

I came to appreciate, gazing up at the inky black horizon away from city lights, the sprawl of the great square in Pegasus, and the angular sweep of Cassiopea’s “lazy W.” Finding the “dippers” was a guaranteed checkmark by two of the required constellations, for Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. But my favorite of all was the Pleiades.

For the uninitiated, the seven stars making up the main part of the Pleiades can often be mistaken as the Little or Big Dipper. But the tight cluster, visible to the naked eye and rising late in the summer sky or high up in autumn in Taurus, is unmissable once you learn it.

Thing is, of course, it’s not a constellation, officially, but an asterism that is part of the constellation Taurus. Which makes this fourth edition of our new series, Here, There & In My Chair, a turn to take a look at this famous open cluster, after spending time on a nebula, globular cluster, and planet earlier. Here’s to variety!

Here: The Pleiades Shining Bright in Autumn

Like our discussion of Jupiter and its moons, Galileo factors in again with the Pleiades, being first to look at the cluster with a telescope. He shared a sketch of the Pleiades in his 1610 treatise, Sidereus Nuncius (Sidereal Messenger), showing about 36 stars.

And Messier of course comes along, as with any other deep space object on his famous list, logging the Pleaides as number 45 on March 4, 1769. But knowledge of the cluster dates back to antiquity:

The cluster was mentioned in the works of Homer (Iliad and Odyssey, 750 B.C. and 720 B.C.), the prophet Amos (750 B.C.) and Hesiod (700 B.C.) among others.

In Greek mythology, the cluster represents the Seven Sisters, companions of the goddess Artemis and daughters of the sea-nymph Pleione and the Titan Atlas, who held the celestial spheres on his shoulders. …

The Greeks oriented two famous temples on the Acropolis of Athens – Hekatompedon (550 B.C.) and Parthenon (438 B.C.) – to the rising of the Pleiades.

The cluster’s rising before dawn in early June has long been considered as the beginning of the new year by the Māori in New Zealand, where the Pleiades are known as Matariki and their rising is celebrated at a midwinter festival.

The earliest depiction of M45 was found on a bronze age artifact dating back to 1,600 B.C. The artifact is called the Nebra sky disk and it was discovered near Nebra in Germany.

The cluster is mentioned as Khima in the Bible three times: Amos 5:8, Job 9:9, and Job 38:31.

Persians knew the cluster as Soraya and its Japanese name is Subaru, which means “coming together” or cluster. The Vikings saw the Pleiades as Freya’s hens, while the Celts associated the stars with mourning because they rose in the eastern sky in the evening around the winter solstice, which coincided with a festival devoted to the remembrance of the dead.

In Arabic, M45 is known as al-Thurayya and mentioned in a number of ancient texts.

Babylonian astronomers new the Pleiades as MUL.MUL, “star of stars.” In Babylonian star catalogues, the Pleiades head the list of stars seen along the ecliptic as they were located near the vernal equinox in the 23rd century B.C.

In Hinduism, the cluster is known as Krittika, referring to the six sisters who raised the war god Kartikeya. The Chinese know M45 as the Hairy Head of the White Tiger of the West.

Native American cultures used the cluster to measure keenness of vision by the number of stars the observer could see it in. The Aztecs based their calendar on the Pleiades, with the cluster’s heliacal rising marking the beginning of the year. A number of other indigenous peoples of the Americas associated the Pleiades with various myths and legends.

As an asterism it is visible nearly all over the world, from the North Pole to farther south than the southernmost tip of South America.

There: Young, Hot Blue Stars Swimming in Nebulosity

The Pleaides lies about 445 light years from Earth, and formed relatively recently, about 75 million to 150 million years ago. Around 1,000 stars are considered part of the open cluster, which is dominated by young, blue stars. Burning hot and fast, their lifespans total just a few hundred million years, compared to the billions of years stars like our Sun last.

As a gravitationally-bound group, the Pleaides is moving through space toward the feet of Orion, which it is expected to reach in about another 250 million years, after which the stars will separate and migrate, pulled by the stronger gravity from other objects. It is thought our own Sun formed a group like the Pleaides before claiming its own area of space.

The name Pleaides most likely derives from the Greek word plein, meaning to sail. The cluster’s annual reappearance coincided with the beginning of sailing season in the Mediterranean.

Mythological parent stars Atlas and Pleione are joined by their seven daughters to form the bright, blue family of nine visible from October through April.

From https://www.messier-objects.com/messier-45-pleiades/:

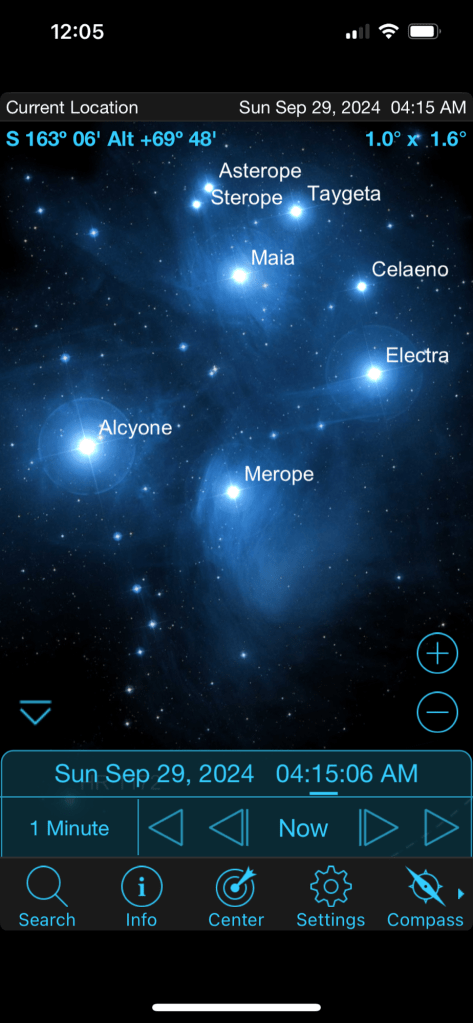

The brightest stars in the Pleiades cluster are Alcyone (apparent magnitude 2.86), Atlas (3.62), Electra (3.70), Maia (3.86), Merope (4.17), Taygeta (4.29), the variable star Pleione (5.09), Celaeno (5.44), and Asterope (5.64, 6.41).

In My Chair: Spying the Pleiades from Inside the Cluster

The legend of the Pleaides is so long, and rich, and the wide-angle view from Earth so familiar and compelling that it’s not often I consider individual stars in the family.

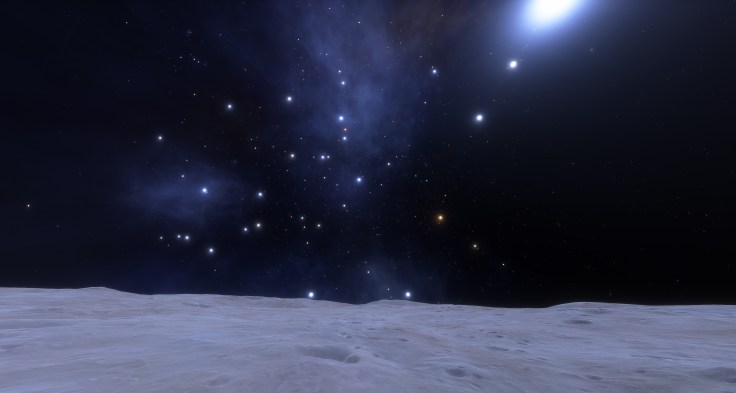

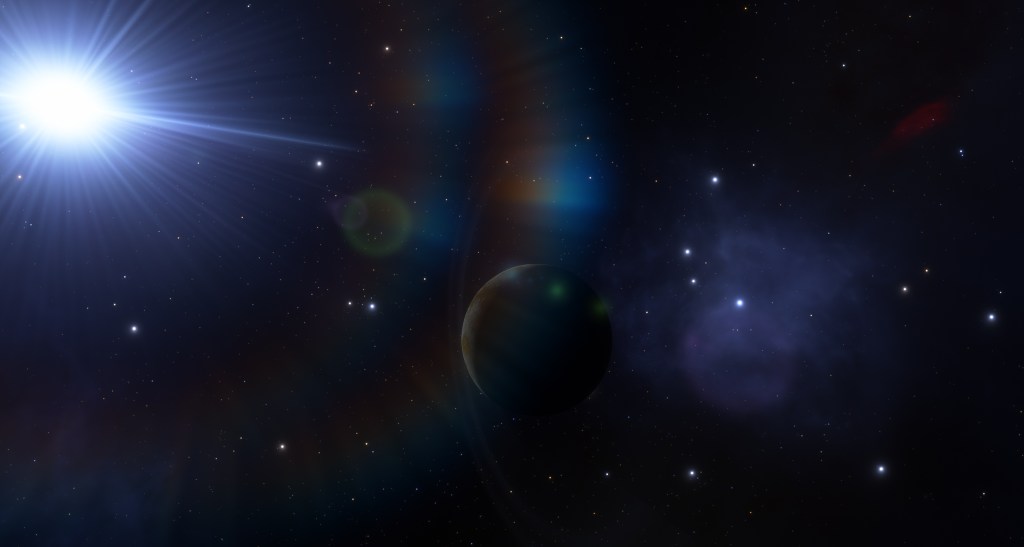

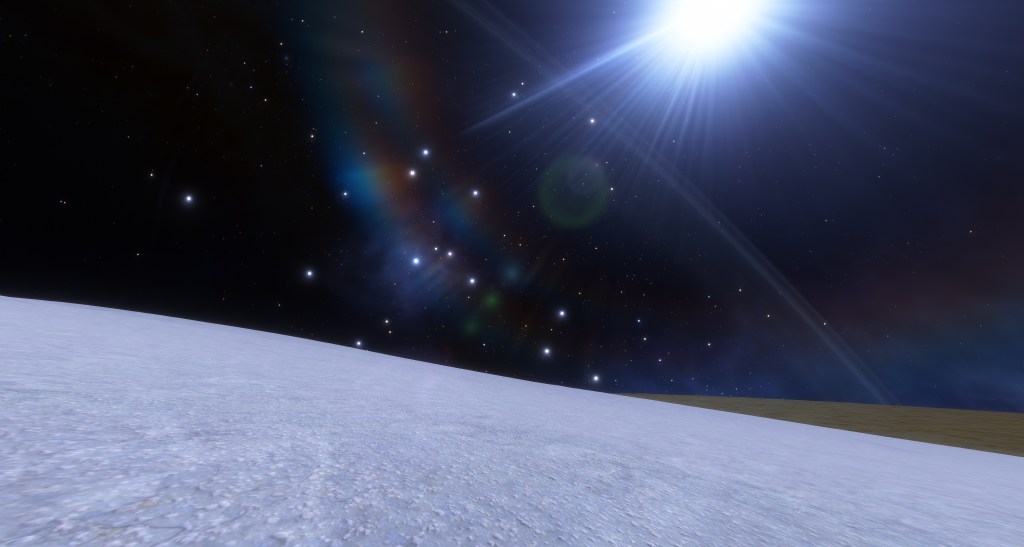

But with the power and magic of Space Engine, I can fly to any one of the bright, blue suns and visit (procedurally-generated) planets orbiting them to spy the dazzling cluster from the inside.

Landing on a moon in the Electra system, you can look outward at other young blue stars training nebulosity — or, otherwise, blowing dust and gas through space with their solar wind — and even spy angry red Betelgeuse occupying the same sky.

From a snow-capped peak on a planet orbiting Merope a similar view awaits, albeit with a more earthly landscape to set off against the blazing fireworks.

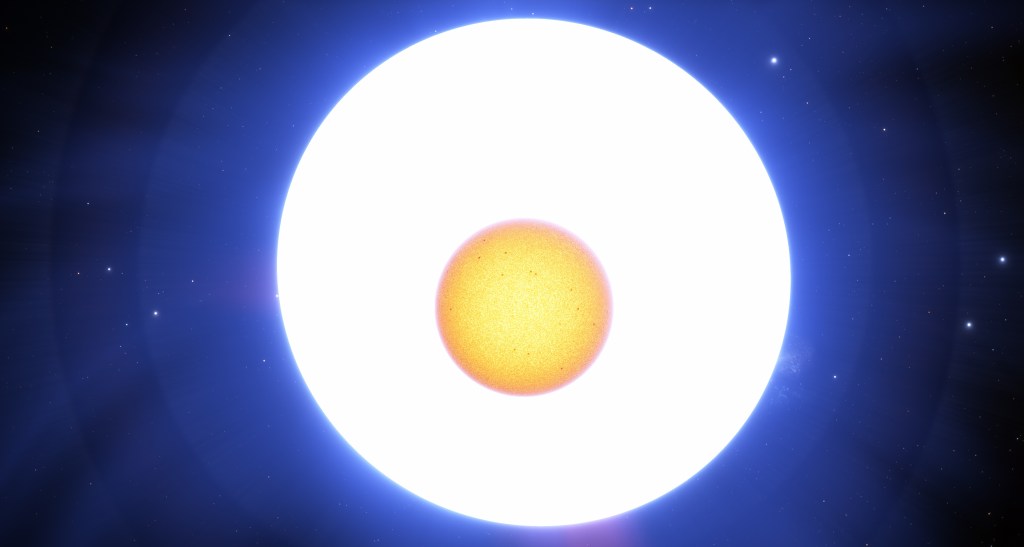

Alcyone, up close, revealed itself to be a triple star, with smaller golden and blue-hued companions joining the big, white-blue primary star. (A reminder: with these galleries, click on a photo so you can see them nice and big!)

I am a big fan of the Nebra Sky disc (https://dcwalley.com/sky-disc), but the Lascaux caves probably have the earliest depiction of the Pleiades. It shows 7 dots in about the right position in what could be a depiction of Taurus.

https://www.inyourpocket.com/johannesburg/wonders-of-rock-art-lascaux-cave-and-africa_13269e

LikeLike